Over the past few years, Google have aggressively suppressed concerns and discussions amongst its employees who opposed the company’s rapid transformation into a digital arms dealer. And as things stand, one of their first major military contracts has made them complicit in genocide. This is a description of worker organising at Google, and of the repression that ensued in response.

In April 2021, a self-organised group of workers at Google and Amazon came together to form No Tech for Apartheid (NoTA). These workers were organising in response to Project Nimbus, a $1.2 billion cloud services contract between their employers and the Israeli government and military.1 In response, they faced massive repression, and the more outspoken organisers were forced to resign.2 Yet after the events of 7 October 2023, and the commencement of Israel’s brutal assault on the Gaza Strip, it became clear to many of us that it was highly likely that Google Cloud and Google’s AI platforms were being used in carrying out large-scale human rights violations.3 Consequently, we renewed our efforts to organise with NoTA.

The first months of 2024 were decisive. In January, the International Court of Justice had already provided an advisory opinion, stating that it was plausible that Israel was committing a genocide in Gaza, and invoking member states’ obligations to prevent genocide. Not two months later, Google fired another one of our organisers.4 In early April, the world learned about Project Lavender and Where’s Daddy, the artificial intelligence tools used by the IDF to target Palestinians in Gaza.5 And ten days later, we found out that Google had agreed to provide the Israeli Ministry of Defence with access to Google Cloud’s Big Data and AI services.6 The Ministry, which maintained that Project Nimbus was “not directed at highly sensitive, classified, or military workloads relevant to weapons or intelligence services”, was even given a 15% discount on consultations.

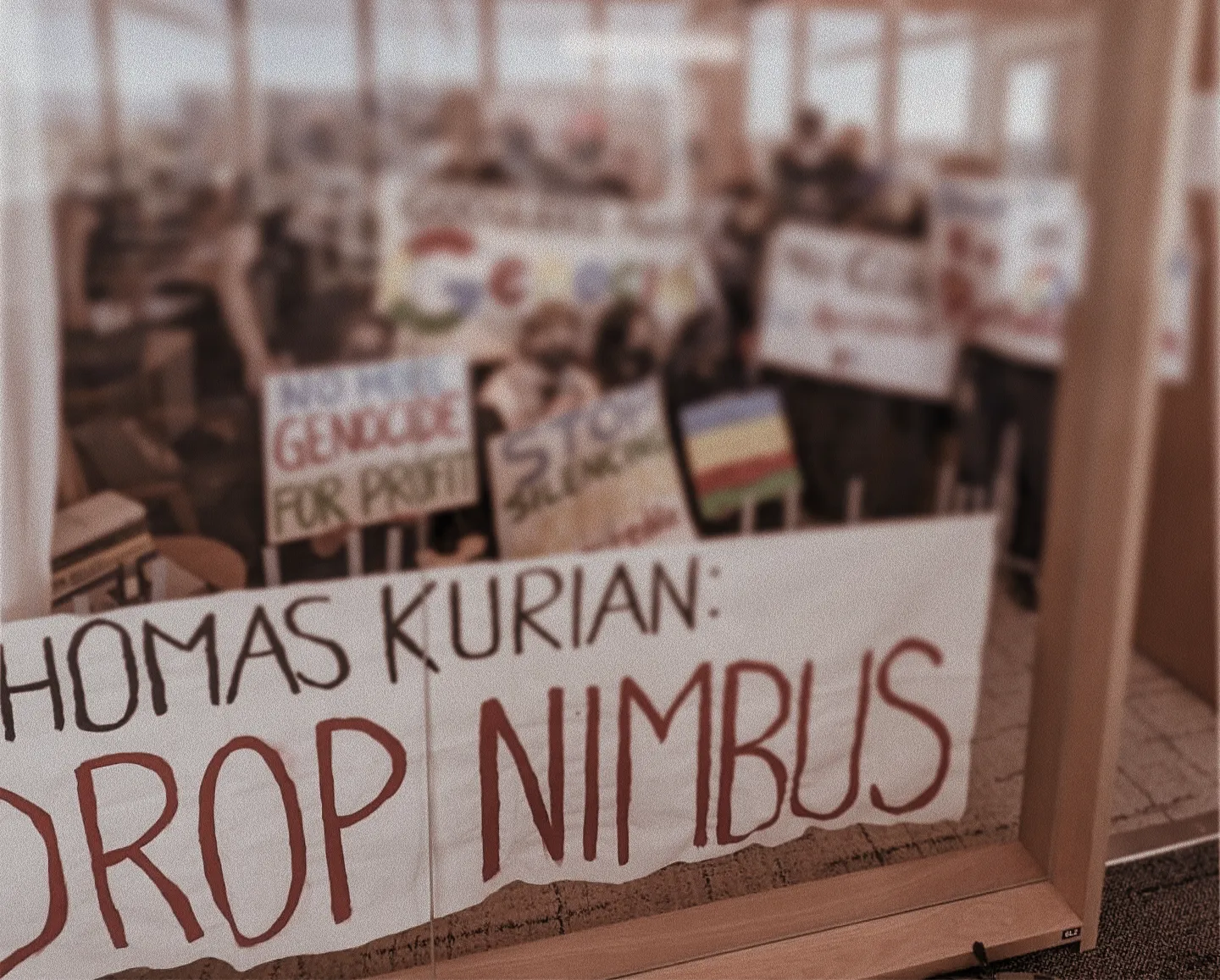

It was clear to us at this point that a genocide was unfolding, and that Google were materially involved. Workers at NoTA therefore decided to organise a livestreamed sit-in to force Thomas Kurian — the CEO of Google Cloud — to meet with us and discuss three demands: drop Project Nimbus; bring an end to the discrimination and harassment of our Palestinian and Muslim colleagues; and address the doxxing and retaliation against workers who spoke out.7

The demonstrations were met with further repression. Google tried to get workers at the sit-in arrested; likely at Kurian’s behest.8 By the end of April, they had fired a total of 50 employees, including workers who were just distributing flyers or were only marginally associated with the protests.9 They justified the firings by claiming that protestors had defaced property and physically impeded the work of other employees. This was a complete fabrication. Shortly after the firings, employees also received a threatening email from Chris Rackow — Google’s head of security, with former ties to the Navy SEALs and the FBI.10 They were informed in no uncertain terms that if they thought Google would overlook such conduct, they had better “think again”. In a concurrent email sent by Sundar Pichai, employees were informed that Google was a business, not a place to debate politics. Borrowing from the tactics used ad nauseam by universities across the U.S. and Europe, Pichai maligned the protests as making other workers feel unsafe.11

The message was clear — employees were to keep their heads down and stay silent, even when their work was being used to enable genocide.

This was not, of course, the first time Google have seen internal protests against military contracts. In 2018, workers protested against Project Maven, a machine learning contract between Google and the Department of Defence.12 As with Nimbus, Google had initially lied about the scope of the project; it took internal leaks to make it clear that the project entailed training AI systems that would use drone imagery to make targeting decisions.13 These revelations sparked heated internal discussions, resulting in petitions that were signed by thousands of workers.14

The more permissive political climate at the time meant that workers were less afraid to speak out, and felt that they could discuss their concerns with their managers, and that they were being listened to. The protests ended up being broadly successful. Google announced that Project Maven would end in 2019, when the original contract expired, and a set of nebulous “AI principles” was introduced to placate worker discontent — a core promise being that Google would not develop or deploy artificial intelligence for weaponry and surveillance, or for projects that would violate human rights.15 This victory was, however, marred by a simultaneous statement issued by Kent Walker — Google’s President of Global Affairs, better known today as their public face, amidst the antitrust lawsuits against them. Walker was quick to reassure the Pentagon that Google were “eager to do more”, and that the cancellation of Project Maven would not hinder their other work with governments and defence departments around the world.16

Indeed, shortly thereafter, company policies and internal structures were altered to avoid a repeat of the Project Maven embarrassment. “Communicate With Care” — Walker’s brainchild — was an elaborate cover-up scheme that involved automatically deleting internal chat messages, and labelling routine emails as being under attorney-client privilege.17 And after Project Maven’s cancellation, Walker went on to institute Google’s internal need-to-know policy, in order to control what information could and could not be shared amongst teams.18 The policy was also accompanied by new community guidelines that discouraged discussing politics at work. All in all, this was an assault on Google’s hitherto relatively open culture of internal information sharing; an attempt by management to preempt any further leaks on ethically questionable projects.

The next change that Google’s executives enforced was to consolidate power at the very top of the reporting chain. Part of the reason the protests against Maven were successful was that many senior directors and vice-presidents had been receptive to employee concerns. By the time Nimbus came around, the power to address these concerns — or even to discuss them — had long been stripped from the same managerial class, whose job roles had been reduced to the handling of routine administration. Google also ramped up its policing of internal mailing lists and meme-sharing websites, which had served as a portal to critique company policies.19 Any mention of the word “genocide” would get emails and memes removed by moderators; and at one point, even the word “killed” — especially in the context of Gaza — could get a post removed. Once again, the justification was that these posts might distress employees. And by the end of 2024, Google’s clampdowns had reached the point where all offices now featured a “no unauthorised posters” policy. Repeated offences could lead to managerial involvement or to a meeting with HR. It had effectively become close to impossible to find discussion of Project Nimbus on Google’s internal networks — particularly ironic for a company that publicly claims to be organising the world’s information and making it accessible. Nevertheless, Google workers continued to try and share information by flyering, postering, or even writing URLs to discussions on office whiteboards — all approaches that were now prohibited under the new policy.

Ultimately, the tech industry’s broader job malaise also played a significant role in silencing many employees. In 2022, Google joined the rest of the tech world in announcing mass layoffs; a year later, they laid off another 12,000 workers.20 This malaise provided executives with extra leverage over employees — after all, who would want to voice their opinion regarding their employer’s complicity in genocide, with the sword of unemployment always hanging over their heads?

All these challenges notwithstanding, NoTA have continued to work against Project Nimbus. Our members have used communication and organisational tools outside the corporate network to organise effectively and safely. We have found increasingly creative ways to reach our colleagues and to share a steady stream of reports on Google’s complicity in the genocide. We have worked with Francesca Albanese — the UN Special Rapporteur on the Occupied Palestinian Territories — to document this complicity.21 And our information campaigns have pushed Google DeepMind — Google’s cutting-edge AI research department — to suppress its workers’ unionisation efforts; efforts aimed at preventing the use of DeepMind’s work by the IDF and by militaries in general.22

Yet the central obstacle facing tech workers is not the difficulty of consolidating or sharing information, however deliberately companies may try to obstruct this. Our biggest challenge is that the tech industry has little history of unionisation. Project Nimbus represents the first experience of organised labour for many tech workers. With support from organiser networks and established unions, we have focused on providing organiser training to those getting involved. This work is essential because, if we are ever to succeed, meaningful relationships must be built among workers who have been systematically isolated and fragmented into silos. Workers must also come to recognise the collective power they hold, even in the face of explicit threats to their livelihoods.

This is particularly true given the specificities of the cloud services provided by Google, Amazon, and Microsoft. First, it is precisely these services that are presently implicated in war crimes. Google own everything in their cloud platform “stack” — they rent out platform access to their customers, amongst whom we find the Israeli military. Google executives have routinely resorted to platitudes when asked for accountability: customers must follow Google’s Acceptable Use Policy; the use of Cloud services to harm people is explicitly prohibited; and so on. However, as Microsoft’s recent admissions reveal, the ability to actually verify that these policies are being respected is directly at odds with the data privacy policies that these cloud platforms offer, making it impossible for companies to even know how their platforms are being used.23

Second, working on these services actually affords workers significant leverage. Cloud platforms differ from other dual-use technologies — such as communication hardware, computer chips, or conventional software — in that they are not simply designed, shipped, and deployed. They are live infrastructures that require continuous human labour to stay functional. Software engineers, site reliability engineers responsible for monitoring uptime, network and hardware engineers who keep data centres operational, are all indispensable to this ongoing maintenance. This serves as a source of worker power: without labour, these systems will come to a grinding halt. Through NoTA’s organiser training efforts, we have been able to bring hundreds of Google workers into the organisation over the past two years, mobilising them to participate in actions and campaigns, and making this power visible through political education and organising.

NoTA continue to work toward the cancellation of Project Nimbus. The stakes today, however, extend well beyond that one contract. Since Donald Trump’s election, Google have moved rapidly to consolidate their position as the primary provider of the infrastructures of surveillance and oppression. In just the months following the inauguration, they have abandoned their pledge to not use artificial intelligence for surveillance or weaponry; they have begun work with US Customs and Border Protection to augment the southern border’s surveillance infrastructure (provided by Elbit) with AI capabilities; they have entered into an AI Lab partnership with Lockheed Martin, to use AI in targeted weapon systems; they have unveiled a collaboration with Palantir to accelerate the deployment of Google Cloud for sensitive government and military applications; and they have provided ICE with data about Palestine activists in the United States.24

Google, like most Israeli arms manufacturers, have discovered the utility of the “Palestine laboratory”; of using Palestinians as test subjects for their surveillance and digital arms infrastructures.25 They hope, no doubt, that the use of these technologies in Gaza will serve as marketing material when the time comes to sell to the next oppressive government or military. Opposing this project of domination — particularly when it comes to surveillance and weaponry — requires us to harness multiple forms of power and resistance. Thus, while NoTA continue to build power on the inside, we are also looking to build ties with students, activists, academics, AI practitioners, and human rights organisations to pressure Google from the outside. Our collective freedom and our future depend upon it.

Free Palestine. Free all of us.

Notes

-

Amitai Ziv, “Israel Picks Google, Amazon for Massive Official Cloud; ‘Data Will Remain Here’”, Haaretz, 21 April 2021. [^]

-

Nico Grant, “Google Employee Who Played Key Role in Protest of Contract With Israel Quits”, The New York Times, 30 Aug 2022. [^]

-

The IDF later claimed that they would not have been able to continue their operations in Gaza without the help of public cloud platforms, since their internal cloud systems were getting overloaded. See: Yuval Abraham, “‘Order from Amazon’: How tech giants are storing mass data for Israel’s war”, +972 Magazine, 4 August 2024. [^]

-

Billy Perrigo, “Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel”, TIME, 10 April 2024. [^]

-

Yuval Abraham, “‘Lavender’: The AI machine directing Israel’s bombing spree in Gaza”, +972 Magazine, 3 April 2024. [^]

-

Billy Perrigo, “Exclusive: Google Contract Shows Deal With Israel Defense Ministry”, TIME, 12 April 2024. [^]

-

Wendy Lee, “Google employees stage sit-ins to protest company’s contract with Israel”, Los Angeles Times, 16 April 2024. For the livestream, see: https://www.twitch.tv/notech4apartheid/clip/BloodyExquisitePigDogFace-wRpiAtkw4wWAfByl [^]

-

Hayden Field, “Google workers arrested after nine-hour protest in cloud chief’s office”, CNBC, 17 April 2024. [^]

-

No Tech For Apartheid Campaign, “STATEMENT from Google workers organizing with the No Tech for Apartheid campaign on Google’s firings of 50 total workers”, Medium, 23 April 2024. These firings included a Palestinian worker who had briefly stopped by to show his support. See: Chloe Berger, “Ex-Googler and Palestinian-American fired for opposing Project Nimbus speaks out: ‘This was not my idea of what the American workplace should be’”, FORTUNE, 23 April 2024. [^]

-

Alex Heath, “Google fires 28 employees after sit-in protest over Israel cloud contract”, The Verge, 18 April 2024. [^]

-

Robert Hart, “Google Fires More Workers Over Israeli Cloud Contract Protest After CEO Says Leave Politics At Home”, Forbes, 23 April 2024. [^]

-

Azad Essa, “‘Google chooses apartheid over justice’: Workers protest against Project Nimbus”, Middle East Eye, 9 September 2022. [^]

-

Lee Fang, “Leaked Emails Show Google Expected Lucrative Military Drone AI Work to Grow Exponentially”, The Intercept, 31 May 2018. [^]

-

Scott Shane, Cade Metz & Daisuke Wakabayashi, “How a Pentagon Contract Became an Identity Crisis for Google”, The New York Times, 30 May 2018. [^]

-

Erin Griffith, “Google Won’t Renew Controversial Pentagon AI Project”, Wired, 1 June 2018; Devin Coldewey, “Google introduces ‘AI principles’ that prohibit its use in weapons & human rights abuses”, Business and Human Rights Centre, 18 July 2018. [^]

-

Sydney J. Freeberg Jr., “Google To Pentagon: ‘We’re Eager To Do More’”, Breaking Defense, 5 November 2019. [^]

-

“Amid New Complaints from State AGs and Federal Judges, CA Bar Must Investigate Google’s Kent Walker”, American Economic Liberties Project, 3 June 2025. [^]

-

Nick Bastone, “Google’s new community guidelines tell employees not to talk politics on internal forums or bad mouth projects without ‘good information’”, Business Insider, 23 August 2019. [^]

-

Nico Grant, “Google to Tone Down Message Board After Employees Feud Over War in Gaza”, The New York Times, 8 April 2024. [^]

-

Q.ai, “Google Layoffs: Big Tech Continues Downsizing”, Forbes, 23 November 2022; Adam Satariano & Nico Grant, “Google Parent Alphabet to Cut 12,000 Jobs”, The New York Times, 20 January 2023. [^]

-

Harriet Williamson, “UN Calls Out Google and Amazon for Abetting Gaza Genocide”, Progressive International, 26 August 2025. [^]

-

“DeepMind UK staff plan to unionise and challenge deals with Israel links, FT reports”, Reuters, 26 April 2025. [^]

-

Harry Davis & Yuval Abraham, “Microsoft blocks Israel’s use of its technology in mass surveillance of Palestinians”, The Guardian, 25 September 2025. [^]

-

See: Lucy Hooker & Chris Vallance, “Concern over Google ending ban on AI weapons”, BBC News, 5 February 2025; Sam Biddle, “Google Is Helping the Trump Administration Deploy AI Along the Mexican Border”, The Intercept, 3 April 2025; “Lockheed Martin and Google Cloud Announce Collaboration to Advance Generative AI For National Security”, Google Cloud, 27 March 2025; Leigh Palmer, “Google Public Sector and Palantir collaborate to bring Google Cloud to FedStart”, Google Cloud Blog, 23 April 2025; Shawn Musgrave, “Google Secretly Handed ICE Data About Pro-Palestine Student Activist”, The Intercept, 16 September 2025. [^]

-

Antony Loewenstein, The Palestine Laboratory: How Israel Exports the Technology of Occupation Around the World, 2024. [^]